Review: Montaigne - Essays

Portrait of Montaigne

“Montaigne was persuaded that everything had already been thought and said, and was anxious to show that man is always and everywhere one and the same.”

I recall, upon reading the first essay, I thought to myself, “So Montaigne will touch upon a wide range of topics, but not go very in-depth?” This is true for the shorter essays; but, like I have discovered of most things, the longer ones are better.

They are not just a series of essays about various topics, philosophical or otherwise; they are not just the best endorsement for one to read the ancient Greek & Roman authors; the Essays paint a tender, and detailed portrait of this great Renaissance Humanist, and Skeptic.

Montaigne writes in a discursive manner, which I personally enjoy. It reads as very down-to-earth; very conversational. He is very good at adding a human touch to matters great and small.

You will get an extra "something" out of the essays if you have a certain amount of kinship with Montaigne, if you share some of his views; he puts so many forth that you will no doubt find that you share something in common. That was one of his aims in writing the essays in fact; to find a friend, a kindred spirit. As I read, I realised we shared many similarities; a love for the ancient Greeks & Romans (especially the latter) being but one.

I remember the essay where he really grabbed my attention: Book I, Essay XXVI: Of the Education of Children. I thought that there is more to this man than has been displayed through the previous essays.

Those who, as our custom is, undertake to direct several minds of such diverse measure and structure with the same lessons and similar rules of conduct - it is no wonder if, among a whole multitude of children, they find only two or three who produce any sound fruit from their teaching. —Bk. I., Ess. XXVI

Let him make him sift every thing, and lodge nothing in his brain on authority merely and on trust; let not Aristotle's principles be his principles, any more than those of the Stoics or Epicureans; let this diversity of opinions be put before him: he will choose if he can; if not, he will remain in doubt. None but a fool is sure and determined. —Bk. I., Ess. XXVI

Education is something very dear to my heart, and it’s by random events of fortune that I have become aware of the classic pieces of literature, ancient and modern. We both share the opinion that the (mass) educational systems are not very good. I thoroughly believe that people’s lives can be changed, truly changed, by education, and it’s one of the great misfortunes that most people, though possessing the potential, aptitude, affinity, or interest, will never pursue or learn deeply about subjects that they potentially have a deep interest in throughout the course of their life.

He who has not directed his life in general to a certain end, for him it is impossible to adjust the separate acts; for him it is impossible to arrange the pieces, who has not a figure of the whole in his head. —Bk. II., Ess. I

I care little for new books because the old ones seem to me fuller and stronger." —Bk. II., Ess. X

Not having been able to do what they desire, they have made a show of desiring what they were able to do. —Bk. II., Ess. XIX

They who study without books are all in the same plight. —Bk. III., Ess. III

Books have many agreeable qualities for those who know how to choose them. —Bk. III., Ess. III

Let us set aside the common people,- ‘Who snore, though awake . . . for whom, living and seeing, life is almost death.’ (Lucretius III, 1048, 1046) who are not conscious of themselves, who do not judge themselves, who let most of their natural faculties lie idle. —Bk. II., Ess. XII

The central theme throughout many of the Essays is the study of himself. And that is what I think Montaigne would have liked the reader to do; to study themselves. Engage in meta-cognition. Think about what you are doing. Be aware of your faults. Reform them. Aspire to be the best possible version of yourself as you can. Live according to Nature. Ignore how you appear to other people’s eyes; care only about how you look in your own:

In every thing and everywhere my eyes are enough to keep me straight; there are no others which watch me so closely or which I more respect. —Bk. I., Ess. XXIII

Let him be able to do everything, but enjoy doing only the best things —Bk. I., Ess. XXVI

It is many years that I have had only myself for the target of my thoughts, that I have observed and studied myself alone; truly, if I do study any thing else, it is only to fit it immediately upon myself, or, to say better, within myself. —Bk. II., Ess. VI

By diligence, by study, and by art, and have raised it to the highest point of wisdom that it can attain. —Bk. II., Ess. XII

. . . others do not at all see you, they guess about you by uncertain conjectures; they see not your natural disposition so much as your artificial one —Bk. III., Ess. II

I listen graciously and beseemingly to all their reasonings; but so far as I remember, I have never to this hour trusted any but my own. For me, these others are but flitting trifles that buzz about my will. —Bk. III., Ess. II

They who do not know themselves may feed upon underserved approbation; not I, who see myself and scrutinise myself even to my bowels, and who know well what appertains to me. —Bk. III., Ess. V

. . . to wrestle with the defects of my nature and to overcome them by myself. —Bk. III., Ess. VI

. . . but I proposed to myself unattainable standards. —Bk. III., Ess. VII

We defraud ourselves of what is useful to ourselves in creating appearances in accordance with common opinion. We are not so much concerned as to what our existence is in ourselves and in fact, as we are to what is in the public observation. —Bk. III., Ess. IX

Reform only yourself, for there you have full power. —Bk., III., Ess. IX

The most honourable indication of sincerity in such necessity is freely to acknowledge one's own fault and that of others; to resist and retard with all one's might the tendency towards evil; to follow this propension only against one's will; to have better hope and better desire. —Bk. III., Ess. IX

Every one turns elsewhere and to the future, inasmuch as no one turns to himself. —Bk. III., Ess. XII

I study every thing - what I should avoid, what I should imitate. —Bk. III., Ess. XIII

Have you been able to meditate on your life and arrange it? then you have done the greatest of all works... Have you learned to compose your character? you have done more than he who has composed books. Have you learned to lay hold of repose? you have done more than he who has laid hold of empires and cities. Mans great and glorious master-work is to live befittingly; all other things --to reign, to lay up treasure, to build--are at best mere accessories and aids.. It is for small souls, buried under the weight of affairs not to know how to free themselves therefrom entirely; not to know how to leave them and return to them. —Bk. III., Ess. XIII

With the Essays, Montaigne takes you on a journey: into the very heart of his soul, and outward to all manner of subjects, different times, and different people.

Maybe you heard that he quotes a lot from the Ancient Greeks & Romans:

I do not quote others, save the more fully to express myself —Bk. I., Ess. XXVI

I don't know if people exist who do not enjoy these quotations (of course I can understand if this is because they were not translated; you should absolutely get a copy where this is the case) but if they do, that quote (along with many demonstrations of his own defects concerning knowledge) justifies his use of them. The ancients have a great deal to teach us, and reading these essays, if you are not already familiar with the authors he quotes, are a great way to see that.

(He quotes most often from Plutarch and Seneca. I have read Seneca, and can see how much he was influenced by him. I will be reading Plutarch’s Parallel Lives soon, but his essays contain a great many quotations from Plutarch’s lesser-known (what an injustice!) work, the Moralia, or Morals. It’s a shame that I cannot find a complete, physical copy of these on amazon etc., and I hope that the Morals gain wider recognition. I have not yet read these philosophical essays yet myself, but I will absolutely put up with an electronic edition because the quality seems very evident to me. He has also greatly increased my desire to read Lucretius.)

I can't say much more other than Montaigne grew on me the more I read, and I greatly enjoyed getting to know him. Hopefully you do too.

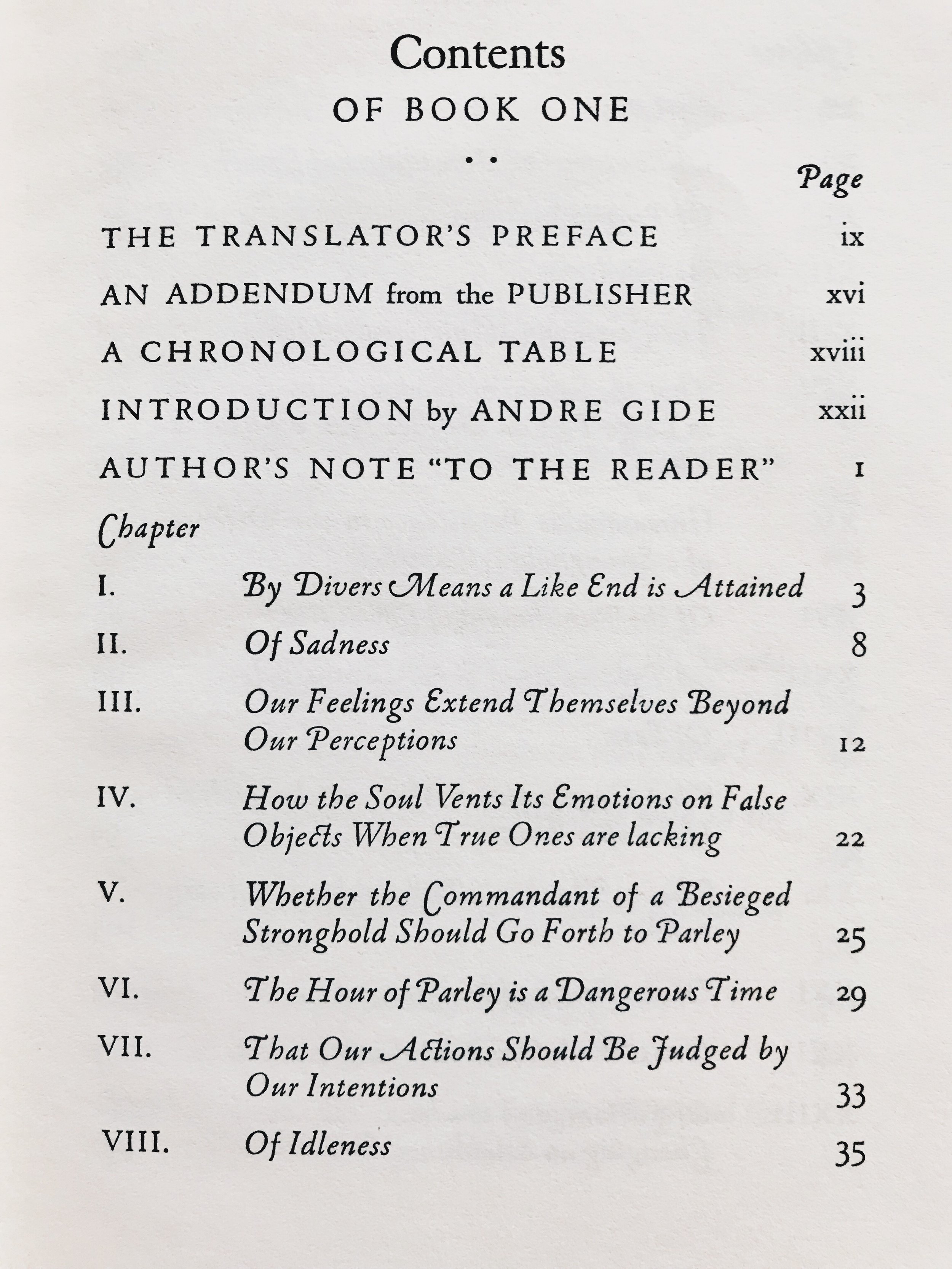

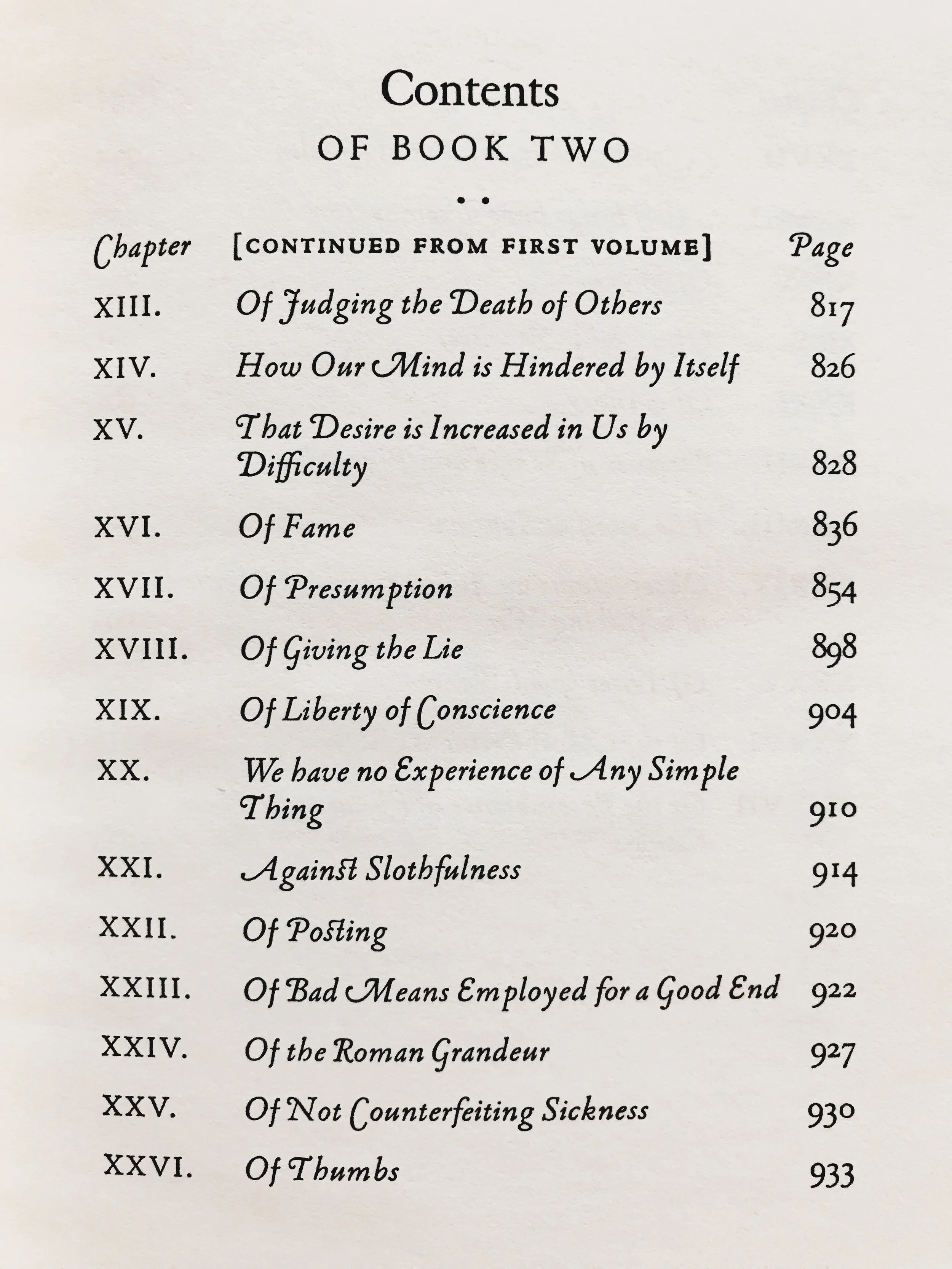

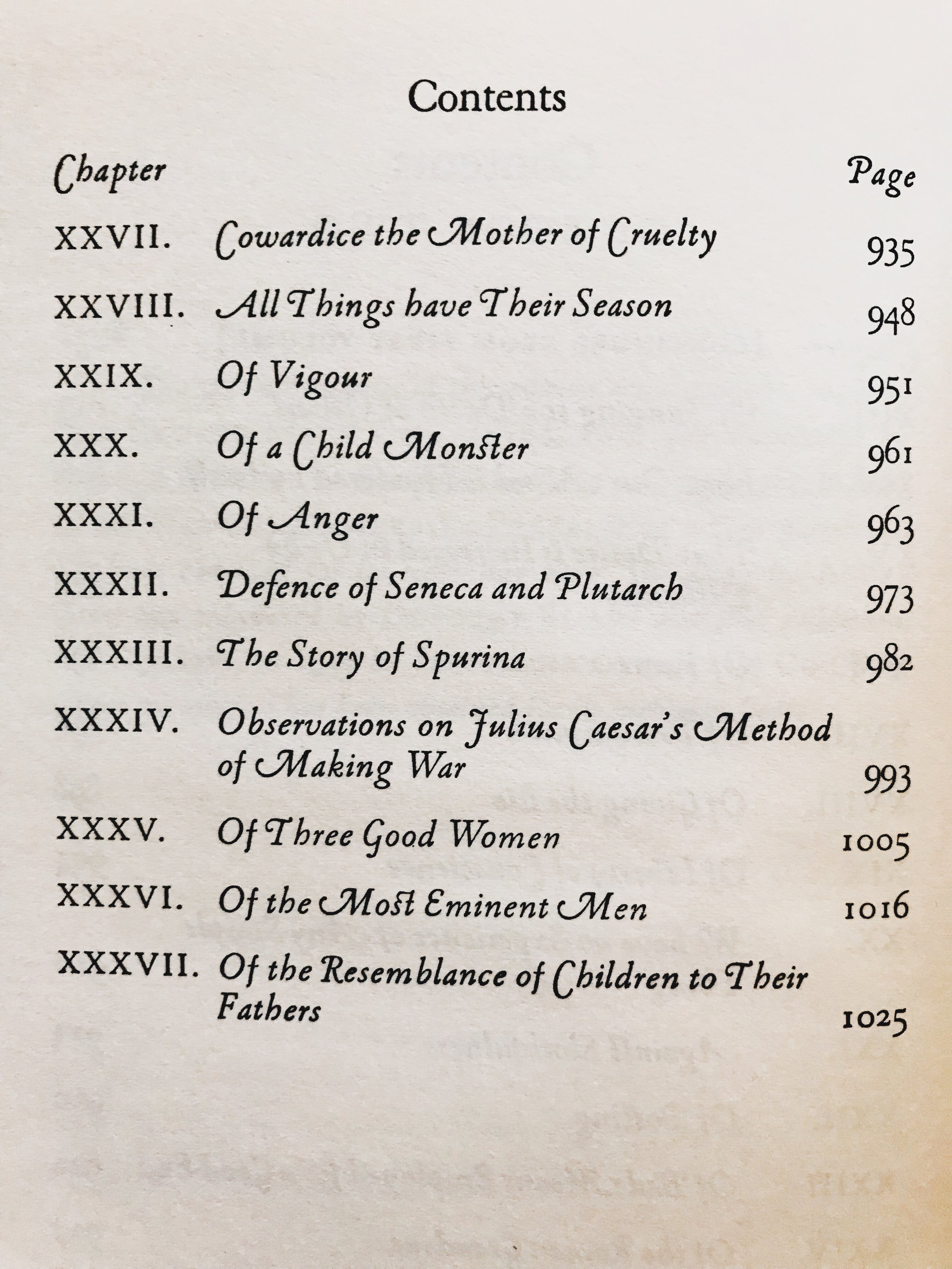

Concerning Translations

I read the Ives translation which was "un-fig-leafed" in a 3 volume edition (including a Handbook to the Essays which incorporated the notes by the translator, and a series of comments upon the Essays by Grace Norton) published by the Heritage Press. I can heartily recommend this edition; the handbook contains sources for every quotation as well as presenting them in their original language, and the comments by Miss. Norton are very incisive and entertaining.

With this translation I really felt like Montaigne himself was talking to me. As the edition I was reading shows, this Ives translation is much better than the others that existed at the time: Florio’s (1603: look this up, it’s definitely not the first translation you should read in my opinion), Cotton-Hazlitt’s (1670-1892), Trechmanns (1927) & Zeitlin’s (1934). I cannot comment on Screech’s.

My favourite essays:

Book I

XXVI - Of the Education of Children

Book II

X - Of Books

XII - Apology for Raimond Sebond

Book III

III - Of Three Sorts of Intercourse

V - On Certain Verses of Virgil

IX - Of Vanity

XIII - Of Experience